As India’s airline market transforms into a duopoly, ticket prices that have long known to be dirt-cheap are climbing.

Airfares on India’s busiest route, Mumbai–New Delhi, were 23% higher during January through August than 2022, according to Thomas Cook India and SOTC Travel. India also saw the highest airfare surge — 41% — in the region in the first three months of this year compared with 2019, a study by Airports Council International Asia Pacific found.

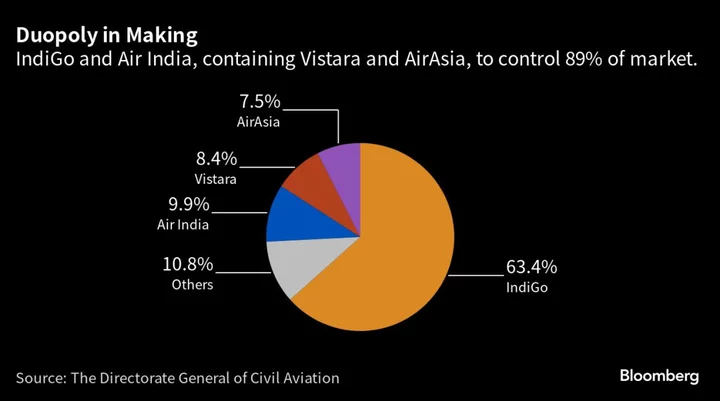

The higher prices come at a time when two domestic carriers — IndiGo and Air India Ltd. — are set to control the bulk of one of the world’s fastest-growing aviation markets, while most smaller rivals struggle to stay afloat in the notoriously competitive market.

IndiGo, India’s biggest carrier with a market share of 63%, is poised to capture more passenger traffic with a record order of 500 Airbus SE. planes, due to join its fleet from 2030. Air India, the country’s No. 2 airline, also made a giant aircraft deal. It will grow bigger with plans to subsume Vistara — currently co-owned by Tata Group and Singapore Airlines Ltd. — by next year, provided it clears antitrust concerns raised. Air India is also acquiring AirAsia’s local unit and merging it with Air India Express.

While big airlines are going bigger, small ones are retreating. Go Airlines India Ltd. stopped flying in May after it went belly up, blaming failing RTX’s Pratt & Whitney engines. Its revival is in limbo as it struggles to attract funding and hundreds of pilots leave the insolvent airline. No-frills SpiceJet Ltd. is also under pressure after reporting losses for the past five years.

“The aviation market in India is transitioning to a few large players,” said Rajat Mahajan, a partner at Deloitte Consulting. “With this consolidation, a couple of airlines are projected to capture about 75% of the market. This leaves a mere 25% for other players, consequently leaving consumers with fewer choices and hence pricier tickets,” said Mahajan, who is also the firm’s travel and hospitality expert.

Rising airfares could threaten Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s goal for bringing air travel to the masses who are financially locked out of the country’s booming aviation. Only a fragment of the world’s most-populous nation can afford flights, while the majority relies on cheaper trains for long distance travel. Just 8.8% of the 1.4 billion population flew domestic airlines last year.

After a surge in prices during the summer, the government urged airlines to keep domestic airfares within reasonable levels, especially on routes that were operated by Go Air and saw the highest fare jump due to a “demand and supply imbalance.”

Cutthroat Market

“A significant chunk of the population is price-sensitive and will find it challenging to accommodate rising ticket prices,” said Mahajan. “The surge in airfares could potentially impact the government’s bid to make air travel more accessible to a wider demographic.”

Modi’s administration in 2016 launched a program to boost regional connectivity by subsidizing ticket prices and linking underutilized airports in smaller towns and remote villages. Its goal is to connect 1,000 new routes, while 469 have been operationalized so far. But the pricey flights could hamper the effort, according to Mahajan.

While expensive tickets are bad for consumers, they can help airlines sustain their post-pandemic bumper profits, boosted by the demand rebound. They are crucial for India’s cutthroat market, where several carriers have collapsed due to fares being too low to cover costs. The graveyard includes former tycoon Vijay Mallya’s Kingfisher Airlines Ltd. and Jet Airways India Ltd.

Another factor driving up prices is inflation in labor and supply chain costs, said Geoffrey Weston, head of global airlines, logistics and transportation sector at Bain. Airlines are cutting new compensation deals to retain employees as they rebuild post pandemic, and bearing high labor costs and attrition in indirect operations such as catering, maintenance suppliers and ground handling, he said.

Global supply chain snarls — exacerbated by the war in Ukraine — have hit aircraft production, resulting in scarcity of available planes. The shortage of spare parts and engine woes have grounded aircraft of airlines from IndiGo and Go Air to Deutsche Lufthansa AG. In addition, the industry is held back by a lack of labor after hundreds of thousands of workers were let go during the pandemic.

This mismatch between the rising demand and shortfall of resources is straining the capacities of airlines and impacting their cash flow generation, Mahajan said, adding carriers are passing steeper operational costs to consumers.

Despite the financial impacts of the pandemic, India’s growing middle class can afford high airfares. Their disposable income has increased, partly boosted by higher savings during lockdowns when spending opportunities were limited. The passenger traffic in India is higher than pre-Covid levels.

“High-growth countries, especially ones with sizeable domestic markets, have come back strongly as underlying dynamics are so positive,” said Weston. Going forward, low prices from budget carriers will play a major role in stimulating demand, he said.

Higher aviation fuel prices also pose a risk to low-cost travel. With Chinese fliers returning to the skies, jet fuel consumption will rise amid tight supplies and result in higher fares. Global oil prices have climbed more than 15% in the past two months.

“As airfares continue to soar, people are more inclined to explore other modes of transport,” said Mahajan. “People might postpone non-essential travel. The demand might taper off once the pent-up or revenge travel subsides.”