The recent softening in the US labor market is hurting Black men the most, threatening to unravel record employment gains made during the pandemic and undo progress for a group that’s been historically underrepresented in the economy.

Black men account for roughly one in five people who have become unemployed since April. It’s a major shift from pandemic-era years that heralded the strongest labor market in decades, particularly for jobs on the goods-producing side of the economy. That impacts jobs in trucking, warehousing and storage that often are held by minority workers. Now, those gains look more like a fleeting moment than a meaningful change.

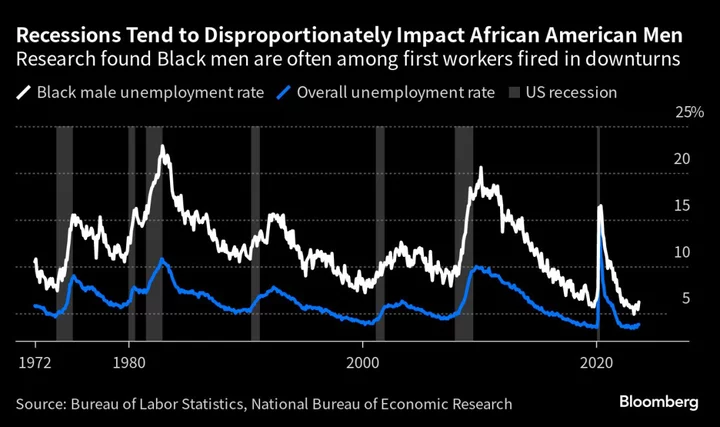

Just five months after briefly touching a record low of 4.9%, the Black male unemployment rate reached 6.2% in September. That stands in sharp contrast with overall joblessness, which continues to hover near a five-decade low. Those broad numbers are evidence to some that the US is achieving the coveted “soft landing,” where central bankers manage to bring inflation back down without causing a contraction. In reality, those figures hide the pain that’s being disproportionately borne by some of those most vulnerable to job losses.

“The pandemic’s impact really shifted the labor market fortunes of Black men in a lot of ways due to the impact on the industrial distribution of workers,” said Michelle Holder, an associate professor of economics at John Jay College, City University of New York.

Now, “the window by which workers could have really gotten really significant wage gains is closing,” she said. “We’re going to go back to this status quo of really tepid wage growth for the immediate future.”

The Federal Reserve is expected to hold its key interest rate at a 22-year high today as it tries to balance economic growth and inflation that remain relatively strong. The central bank’s rate hikes have dented goods consumption as Americans have traded material things for experiences like travel and concerts. That in turn has driven companies to cut jobs in transportation, a sector with one of the highest concentrations of Black male employees.

Giants including FedEx Corp. have shed trucking jobs since last year, while pandemic-star logistics startups like Flexport Inc. flash signs of trouble. Convoy Inc. shuttered operations after a four-month hunt for a buyer failed, and national trucking giant Yellow Corp. declared bankruptcy in August.

Jeremy Charles, a 36-year-old truck driver from Oklahoma City, is on the front lines of this reality. He and 30,000 others worked at Yellow Corp., and Charles hasn’t been able to find a similar paying position since the company's collapse. He’s now delivering food to restaurants and supermarkets, bringing home about $600 less per week despite working more hours.

Read more: Inflation Fight Threatens Fragile Gains for Black Workers

“With Yellow out of business, people understand that a whole bunch of drivers hit the market at once,” said Charles, who started in the industry when wages were soaring in 2021. “People at the bottom like me — who only have one-to-five years of experience — were last to get picked. So we had to step outside the box and try to find something else.”

Increases in Black unemployment tend to be an early recession indicator, given that these workers often lose jobs first. Though some Wall Street forecasters believe the US can dodge a downturn as the economy keeps powering ahead, it already feels like one to many Americans who continue to face elevated prices for essentials and multi-decade high borrowing costs on mortgages and credit cards. Even a mild recession could leave millions of workers — across all demographics — jobless.

Sizable job cuts haven’t materialized yet in other depressed goods-related sectors such as manufacturing, but the pullback in demand is already leading many employers to cut hours to reduce costs.

It’s been a struggle for Ron Stinson, a 50-year-old Columbus, Ohio-native who has been a long-haul truck driver for 30 years.

He was accustomed to a stable market before the pandemic, when he could earn around $3 per mile of driving. That, coupled with fairly stable diesel prices, meant a reliable existence. Rates then surged during Covid due to high consumer demand, but are now down again — sometimes close to $2 per mile.

With the price of fuel staying elevated, “you have to be a mathematician and a magician in order to get that money home to your family,” Stinson said.

At the onset of the pandemic, when unemployment surged to historic levels, Fed Chair Jerome Powell said the central bank wanted to rebuild the gains that Black people and women of color had seen in the labor market in the years prior. The Fed even overhauled how it approached its two mandates of maximizing employment and keeping prices stable, vowing to allow the labor market to run “hot” as long as inflation stayed around its 2% goal.

Read more: The Fed Wakes Up to Race

Industries linked to the goods-side of the economy in particular benefited from that dynamic, with employment in the transportation and warehousing sector up 16.5% since February 2020. Black men, who account for about 16% of workers in those fields, saw their overall share of employment reach levels not seen since 2000.

But the increase in the price of goods over the last two years has been too big to ignore. Policymakers, who now call the labor market out of balance and “too” hot, have hiked the benchmark interest rate to a 22-year high to try to tame inflation.

Holder, a labor market economist who has researched the Black workforce extensively, sees a silver lining: After raising rates aggressively last year, the Fed has delivered smaller hikes that are farther apart this year. That may mean the central bank is able to avoid the kinds of large job losses that have followed other episodes of Fed tightening.

Even still, the outsize job opportunities Black men had in the transportation sector over the past few years weren’t a total win. The jobs themselves tend to be labor intensive and often pay low wages, even before cuts to pay and hours. Recent research from the St. Louis Fed found that despite the recent gains, the wage gap between Black and White male workers hasn’t improved over the past 25 years.

“They weren’t necessarily gaining in terms of wage increases because most of the growth that was occurring, industry wise, that was helping Black men wasn’t happening in a high-wage sector, not even in a mid-wage sector,” Holder said. “It was happening in a low-wage sector.”

Stacey Cowsette, 60, was working as a janitor at a military base in St. Louis when the pandemic hit and he found himself without health care. So he took a second job shipping packages out of an Amazon.com Inc. warehouse.

But as prices started climbing at the fastest pace in a generation, Cowsette soon found out two jobs weren’t enough to make ends meet. He’s also had a difficult time moving up to higher-paying positions.

As the US economy teeters between recession and what economists like to call a soft landing, it’s workers in entry-level positions that could be most easily cut.

“As a Black man, it’s easier to get a warehouse job a lot of times,” said Cowsette, who says he has no plans to retire in the near future. “But to maintain the way of life is kind of hard because you have no incentive to grow.”

--With assistance from Andre Tartar.