Bank of England Governor Andrew Bailey hinted policy makers can’t let up yet in their fight against inflation even as signs amassed that the UK economy is weakening.

Wages are growing too quickly to be compatible with the central bank’s 2% inflation target, and declining pressure on food prices has “got quite a way to go yet,” Bailey said in an interview with the Belfast Telegraph published Friday.

The remarks coincided with official figures showing an unexpectedly sharp drop in retail sales in September and a boom in tax receipts from soaring inflation. Together, the data indicated the searing pressures on prices that the BOE is trying to tackle.

“Persistently high inflation, an unseasonably warm September, and high borrowing costs all point to a depressed consumer with disappearing confidence in the direction the economy is going,” said Charles Hepworth, Investment Director at GAM Investments. “This now appears to be increasingly reflected in voter intent.”

UK two-year yields, which are among the most sensitive to changes in monetary policy, fell four basis points to 4.94%, retreating from a one-month high reached on Thursday. Money markets pared wagers on further interest-rate hikes, placing the chance of a final quarter-point increase by early next year at around 60% compared to 90% earlier this week.

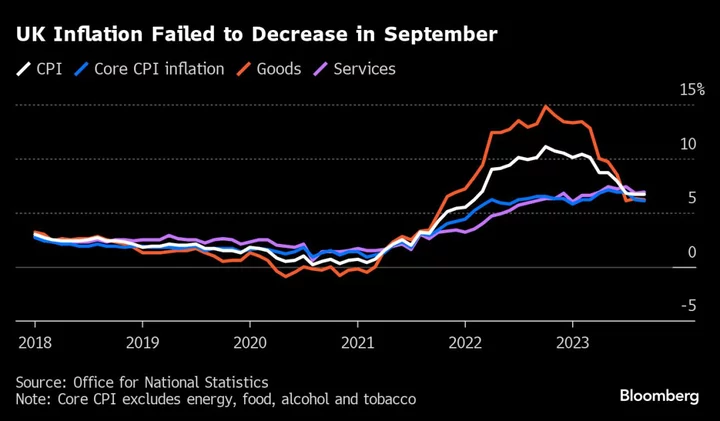

Policy makers are weighing how much more they have to rein in inflation, which is running at more than triple the target. Bailey said he “wasn’t surprised” by Wednesday’s inflation reading that indicated consumer prices rising 6.7% from a year ago in September, the same pace as in August.

This will be welcomed by Prime Minister Rishi Sunak, who has vowed to halve inflation by the end of the year. Bailey said the Bank’s previous forecasts “suggest this could be achieved.”

Bailey didn’t discuss interest rates in the newspaper interview, but he and Chief Economist Huw Pill have signaled that the key lending rate may remain at 5.25% for the foreseeable future until more tangible evidence emerges that inflationary pressures are receding.

He added that he expects inflation to “keep coming down,” despite wage growth which is still near historic highs. “Pay growth as measured is still well above anything that’s consistent with the target,” Bailey said.

The BOE expects a large drop in inflation for October when the next round of figures are published next month. That will reflect a big jump in energy prices a year ago dropping out of the comparison. Falls after that may be more incremental, he said.

Officials delivered the sharpest series of rate rises in three decades to quell price pressures. Data out Friday morning gives a further indication that those increases are hurting consumers, with an unexpectedly sharp drop in retail sales.

The volume of goods sold in stores and online fell 0.9% in September, erasing a 0.4% gain the month before, the Office for National Statistics said on Friday. Economists had expected an 0.4% drop.

That reflected both unusually warm weather, which deterred shoppers from spending on clothes for autumn and winter, and and a dip in spending on luxury items including watches and jewelry.

What Bloomberg Economics Says ...

“The plunge in retail sales in September is reflective of a broader weakening in the British economy. Consumer spending capitulated as elevated interest rates and concerns about the economic outlook curbed spending, while unseasonably warm weather delayed purchases of autumnal clothing.”

—Niraj Shah, Bloomberg Economics. Click for the REACT.

Friday’s figures capped a week of reports pointing toward a slowing economy. Wage growth is ticking down, unemployment has risen, business activity looks weak and consumer confidence has plummeted.

“After September’s higher-than-expected inflation numbers, weak retail sales may help convince interest rate setters that they can afford to wait before moving rates up again,” said Nicholas Hyett, investment manager at Wealth Club.

UK consumer confidence fell the most since the start of the coronavirus pandemic as cash-strapped households felt the impact of persistent inflation and higher interest rates.

GfK Ltd. said its gage of consumer sentiment declined 9 points to minus 30 in October. The drop was the largest since April 2020, which captured the period when the UK started its first Covid lockdown. It’s comparable to the dip experienced after the UK voted to leave the European Union in 2016.

Public finances data also pointed to wrenching pressures on the economy from inflation. An inflation-induced tax boom left UK government borrowing on track to come in significantly below official forecasts this year.

The budget deficit in the first six months of the fiscal year was £81.7 billion ($99 billion) — £15.3 billion above the same period last year but £19.8 billion less than the Office for Budget Responsibility forecast in March.

The shortfall in September alone was £14.3 billion, the Office for National Statistics said, less than the £18.3 billion median estimate in a Bloomberg survey.

The undershoot at the halfway mark of 2023-24 provides a boost for Chancellor of the Exchequer Jeremy Hunt as he prepares for his autumn economic statement on Nov. 22.

The windfall largely reflects the strength of income tax receipts as high inflation boosts both wages and company profits. In its Green Budget this week, the Institute for Fiscal Studies said the deficit was likely to total £112 billion in 2023-24, or 4.2% of GDP, rather than the £131.6 billion OBR forecast.

“Public spending in the UK is particularly susceptible to inflation because a significant proportion of UK government debt is index-linked, meaning interest payments go up with inflation,” said PwC economist Divya Sridhar. “We continue to be optimistic that the government will meet its target to halve inflation by the end of this year. There are considerable gains to be made from a public finances perspective if this target is met.”

--With assistance from Irina Anghel, Aline Oyamada, James Hirai, Mark Evans and Joel Rinneby.

(Updates with comment, Bloomberg Economics and market reaction.)