I’ve spent 10 years of my life thinking my pain wasn’t enough to justify giving it a label. I was diagnosed with fibromyalgia at 16 years old — a disease mostly characterized by chronic pain at the joints and tenderness in specific pressure points — and yet, the diagnosis never felt like enough. Even now at 26, it doesn’t feel like a “good enough excuse,” it doesn’t sound real. Back when I was in high school, I could barely go up stairs or hold my pen. I felt like my teachers didn’t believe me. I didn’t look sick. I was too young to have chronic pain. I was being dramatic. My flare-ups were always convenient. I just hadn’t tried hard enough. Others suffered more, after all. I thought after receiving a diagnosis — an uphill battle of its own — would fix it all. But nothing changed. I couldn’t consider myself disabled because my teachers’ words echoed in my brain. So much so, I confused them with my own thoughts. What I wanted, what I desperately needed, were people willing to help me fight against those thoughts, to build a system around me that encouraged, loved, and accepted me with compassion, instead of invalidating me.

It wasn’t until this year, while writing this, that my perspective on myself, my pain, and my cuerpa began to change. I’ve opened up to my favorite people about my hurt — to my girlfriend, my best friend, and the rest of my chosen family. I requested to join a queer chronic pain support group. I reached out to queer Latine disabled activists for this story. Speaking to them, I felt, for the first time in my life when it comes to my disability, that I wasn’t alone. I wasn’t the only Latine, lesbian, nonbinary Boricua with chronic pain. I now know this is the power of community.

Colonization and capitalism, the two systems that run our reality, are ableist, racist, and homophobic. They’ve tried to change and mold us into the able-bodied, straight, gringo version of ourselves that is most productive. They want to convince us that we’re alone, that no one struggles like we do, and to move through our lives with anger and spite. Our rebellion is this: community healing.

For Latines, religious shame can also factor in; as does the first- or second-gen need to provide and be productive. Whether it’s the trauma of colonization, capitalism, immigration, or all three, it all makes it impossible to spiritually and emotionally heal together, keeping us constantly in isolation. While it’s important to have our solitary moments to self-reflect, there’s a line where that becomes too much. When I give in and spend days in my bed, convincing myself I don’t need anyone, that’s self-sabotage. And it’s not really my fault… our world taught people like me that if we don’t produce, if we’re not useful, then we’re not valuable.

“The assumption is not that there are systemic obstacles that make things impossible for certain people, but that you have to try harder. That it’s on you. You’re the weak one,” Annie Segarra, a disabled queer Latine digital creator and advocate, told Refinery29 Somos. Her numerous diagnoses — Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome and autism, among others — made it extremely difficult to show up in the world the way society expected her to. “I think isolation puts a lot into perspective,” Annie said.

Sometimes that isolation is exactly what’s needed in order to move forward. We have to be able to know ourselves fully before we meet the people that are meant to be in a community with us. Without that, we’re susceptible to others’ invalidation. After high school, finding a job was hell. Disregarding Puerto Rico’s major unemployment issue, a part of me was simply afraid I wouldn’t be able to do it. A friend, whose mom got jobs for some of our other friends, told me doubtfully “you’ll need to stand for the entire shift.” I reassured her I’d be able to do it if I was getting paid. I proved her wrong two years later when I moved to New York and got two retail jobs, secretly suffering. I was determined to be able-bodied, out of spite.

That’s not a healthy mindset, it’s exactly the opposite. “I nearly lost my life trying to be like everyone else. The mask of perfectionism, the mask of people-pleasing, was far too heavy that it nearly killed me,” Mark Travis Rivera, a disabled and queer speaker and founder of AXIS Dance Company, told Somos. While pretending nearly broke him, he says his diagnosis with cerebral palsy, when he was a child, made his own queer acceptance easier. He was already different. “I feel like I had to overcome and say my queerness because my Latinidad, my disabledness, was so apparent in the beginning,” he said.

Gé, Boricua artist and activist, agreed: “We’re here for so many reasons, that are so grand and so sacred, and not to romanticize it, but I feel like being born with diversidad funcional (functional diversity) is what made me queer.” Gé is the partner of one of my closest friends, and we met about a year ago. It’s only recently when they visited New York that I found out they were diagnosed with a brachial plexus injury from birth. They don’t identify as disabled; instead, they refer to themself as someone with functional diversity. It’s not that they’re unable to do anything; it’s that their version of “doing” is going to look different because their body’s different. It’s that simple.

I’m not sure how something that really is so simple caught me so off guard. I’ve never thought about it like that before. I’ve always hated myself for not being able to do what others around me could, so easily — how I walked so much slower and how long it took me to walk up stairs while holding on tight to the handrail. I never considered that I was doing it exactly the same, to my body’s own capacity. Recently, Gé hosted a virtual writing workshop. When I talked to them about how being aware of my body, mindful of it, meant being in pain, I saw them deeply nodding their head. I felt seen.

Having a safe space to express your frustrations, your joy, and all the emotions in between with people that you truly believe care, is essential in healing. I thought I was alone in my pain, thinking no one else could possible understand or care. I was afraid of being vulnerable, opening myself up to them, and getting rejected — so, I dealt with it on my own. Spoiler alert: it didn’t work. As soon as I learned to believe that other people cared for me, everything changed. I decided to believe my chosen family when they said they loved me, after years of not doing so. I didn’t heal right away, and sometimes I still fall back to old habits, but now I know they really are interested in what I have to say, they don’t think I’m dramatic, they don’t entertain my intrusive thoughts and, more importantly, they believe me. I don’t have to prove anything. That’s what la collectiva should work toward.

Finding your community is difficult, especially when you have intersecting identities. It’s not enough to be surrounded by Latine able-bodied people, queer white people, or any other combination. There needs to be a balance. It’s unrealistic to expect everyone you meet to perfectly mirror your experiences or identities. It’s damaging to rely on others’ validation when they haven’t lived what you have.

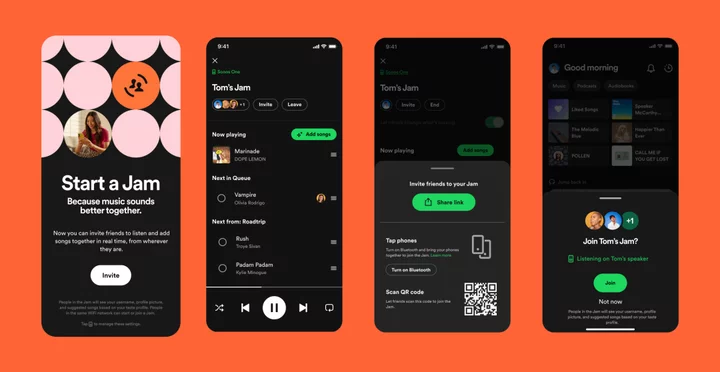

Thankfully, modern times blessed us with the perfect community builder: the internet. I escaped reality by immersing myself in fandoms, whether theorizing about a series on Tumblr or staying up until 3 a.m. reading fanfiction on AO3. Tumblr became my diary, there I released all of my hopes and dreams, sharing them with my online community. “The beauty of technology is here and it’s not going away anytime soon. You can find community through that,” Annie said. “And whether or not that is possible, then there is hope in finding something that nourishes you — even on your own.”

The world at large may be horrible and depressing, but finding people that treat you with tenderness and compassion can change everything. I’ve found mine, and I’m sure there will be more in the future to add to my list of favorite people. But finally… finally, I can include myself there too. That’s what healing in community truly means.