The last nine years have all been the hottest nine years in the nearly 150-year-old modern temperature record. That's not the least bit surprising.

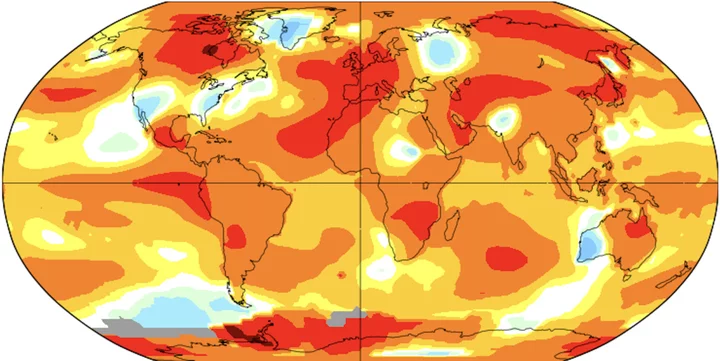

Earth's temperature dial has been turned up. And as a result, heat waves, which are normal, are growing increasingly extreme — which is not normal. That's why large swathes of the U.S., China, and southern Europe are currently experiencing either record-breaking or severe temperatures. (China hit a whopping 126 Fahrenheit on July 16, a new national record.)

Added heat means more record or nearly-record hot weather becoming not just possible, but occurring more frequently. "A barely noticeable shift in the mean temperature from global warming can end up turning a 'once-per-decade' heatwave into a 'once-per-year heatwave' pretty easily," Patrick Brown, a climate scientist at Johns Hopkins University, told Mashable as a past heat wave settled over the U.S.

SEE ALSO: Why the sun isn't causing today's climate change Shifting averages mean more extreme heat. Credit: Climate CentralScientists have repeatedly shown that the frequency and severity of heat waves is increasing, with perhaps a six-fold increase in frequency since the 1980s. The numbers below underscore why this is happening. The world will continue to warm through at least much of the 21st century — but, crucially, just how much is up to us.

Each decade is hotter than the last

Temperature readings and data sets from around the globe — in the U.S., Europe, and Japan — all show an almost identical and considerable rise in Earth's global surface temperature since the 1980s (though the overall global warming trend began decades earlier).

Long term trends are key. And trends are showing each decade is now significantly hotter than the last. "This is expected to continue," the United Nations World Meteorological Organization said.

Different temperature data sets all show an almost identical rise in global temperatures. Credit: WMOCO2 levels are the highest they've been in millions of years

CO2 is the major greenhouse gas trapping heat on Earth and driving climate change (methane plays a prominent role, too). And at some 420 parts-per-million in the atmosphere, CO2 levels are about the same as during the Pliocene or mid-Pliocene, an ancient era when sea levels were around 30 feet higher (but possibly much more) and giant camels dwelled in a forested high Arctic. (Fortunately it takes melting ice sheets and sea levels a longer time to catch up with CO2 levels.) Temperature levels during the Pliocene likely hovered at some 5 degrees Fahrenheit (around 3 degrees Celsius) warmer than pre-Industrial temperatures of the late 1800s.

We're not nearly there yet; globally, Earth has warmed by some 1.2 C (a bit over 2 F), so far. But we could get there, or nearly approach those temperature climes.

"CO2 levels are going to increase," said Dan Lunt, a climate scientist at the University of Bristol who has researched the Pliocene. "We could hit the Pliocene in terms of temperature. But it depends on how rapidly we emit [greenhouse gases]."

CO2 levels haven't been this high since the Pliocene. Credit: NASAGlobal warming is driving astonishing ocean warming

Most of the heat trapped on Earth by the burning of fossil fuels is soaked up by the extremely absorbent oceans (and the oceans pay a high price for this service.)

Between 2010 and 2020, the ocean absorbed (roughly) the equivalent amount of energy released when detonating Tsar Bomba — the most powerful nuclear bomb ever detonated — once every 10 minutes for 10 years. It's an unfathomable number.

"Over 90 percent of heat from global warming is warming the oceans," NASA oceanographer Josh Willis told Mashable. "The amount of warming will change the oceans for the next 50 generations or so," explained Willis.

The sea surface experiences particularly high amounts of warming which can also help drive or sustain heat on land, and stoke life-killing, extreme marine heat waves in the ocean.

Ocean heat content has been relentlessly rising for over three decades. Credit: NOAAHumanity will likely pass a big warming mark

The United Nation's Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) — the global agency tasked with providing objective analyses of the societal impacts of climate change — has concluded that keeping the planet's warming limited to a 1.5-degree-Celsius (2.7 degrees Fahrenheit) rise above 19th century levels would stave off the worst impacts of climate change, like the calamitous impacts of historic rainfall events, mega-droughts, and the melting of colossal ice sheets.

Yet it's now almost certain that humanity will blow through 1.5 C. And keeping temperatures below 2 C, while achievable, will require dramatically slashing carbon emissions.

"At the current rate of progression, the increase in Earth’s long-term average temperature will reach 1.5 °C (2.7 °F) above the 1850-1900 average by around 2033 and 2 °C (3.6 °F) will be reached around 2060," explained Berkeley Earth, a non-profit environmental research organization.

Want more science and tech news delivered straight to your inbox? Sign up for Mashable's Light Speed newsletter today.

All those devastating floods? That's largely because it's hotter.

Warming temperatures boost the odds of heavy, or record-breaking, rainfall.

When air temperature is warmer the atmosphere can naturally hold more water vapor (heat makes water molecules evaporate into water vapor, meaning there's more water in the air, particularly in many humid or rainy regions). Consequently, this boosts the odds of potent storms like thunderstorms, mid-latitude cyclones, atmospheric rivers, or hurricanes deluging places with more rain.

"Once you have more moisture in the air, you have a larger bucket you can empty," explained Andreas Prein, a scientist who researches weather extremes at the National Center for Atmospheric Research. As data shows, this can result in pummeling downpours. "You can release more water in a shorter amount of time — there's very little doubt about that," Prein said.

For every 1.8 degrees Fahrenheit of warming (or one degree Celsius) the air holds about seven percent more water vapor. Earth has warmed by just over 2 degrees Fahrenheit since the late 1800s, resulting in more storms significantly juiced with more water.

In the Northeastern U.S., for example, the amount of precipitation during the heaviest rain events has already increased by 71 percent between 1958 and 2012, and other U.S. regions have seen sizable increases, too.