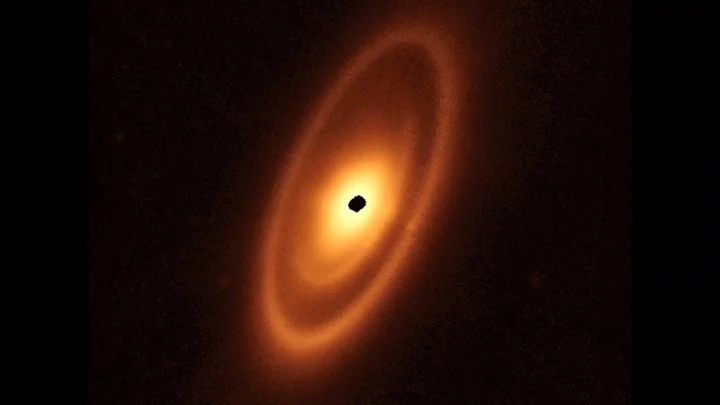

With a little help from the James Webb Space Telescope, astronomers discovered two never-before-seen asteroid belts encircling nearby star Fomalhaut.

Scientists using the joint NASA/ESA/CSA device to image dusty debris discs around Fomalhaut—already famous for being one of the brightest stars in the night sky—were surprised to find the structures are more complex than anything found in our solar system.

Three nested belts extend some 23 billion kilometers from the main star, or about 150 times the distance of Earth from the Sun. The outermost band—previously captured by the Hubble Space Telescope, Herschel Space Observatory, and Atacama Large Millimeter Array (ALMA)—is roughly twice the scale of the Kuiper Belt, a circumstellar disk of small bodies and cold dust beyond Neptune.

The inner belts, also known as debris discs, meanwhile, were revealed for the first time by Webb.

"With Hubble and ALMA, we were able to image a bunch of Kuiper Belt analogues, and we've learned loads about how outer discs form and evolve," according to Schuyler Wolff, a member of the University of Arizona team working on this project. "But we need Webb to allow us to image a dozen or so asteroid belts elsewhere.

"We can learn just as much about the inner warm regions of these discs as Hubble and ALMA taught us about the colder outer regions," he continued. "Where Webb really excels is that we're able to physically resolve the thermal glow from dust in those inner regions. So you can see inner belts that we could never see before."

Fomalhaut's most distant dust ring was discovered in 1983, through observations made by NASA's Infrared Astronomical Satellite (IRAS). The existence of the ring has also been inferred from previous observations using submillimeter telescopes on Hawai'i, NASA's Spitzer Space Telescope, and Caltech's Submillimeter Observatory.

"I would describe Fomalhaut as the archetype of debris discs found elsewhere in our galaxy, because it has components similar to those we have in our own planetary system," lead study author András Gáspár, also of the University of Arizona, said in a statement. "By looking at the patterns in these rings, we can actually start to make a little sketch of what a planetary system ought to look like—if we could actually take a deep enough picture to see the suspected planets."

The newly found inner belts, however, remain something of a mystery. "Where are the planets?" wondered George Rieke, another team member and US science lead for Webb's Mid-Infrared Instrument (MIRI), which made the surprising observations.

Within our solar system, the inner edge of the Kuiper Belt is sculpted by Neptune, while the outer edge is likely shepherded by bodies beyond it. So it's not hard to image that Fomalhaut's rings are similarly shaped by gravitational forces of unseen planets. "I think it's not a very big leap to say there's probably a really interesting planetary system around the star," Rieke said.